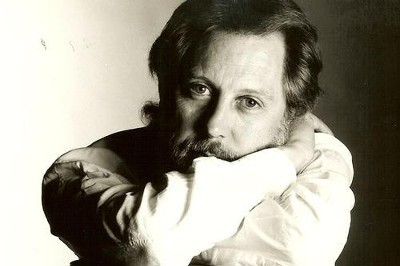

A GREAT COMMUNICATOR. David Puttnam is a British film producer, educator, and environmentalist who recently retired as a member of the House of Lords, where he served on the Labour Party benches for 24 years. His many celebrated film productions include Midnight Express, Chariots of Fire – which won the Academy Award for Best Picture – The Killing Fields and The Mission.

You can listen to this interview as a podcast here.

David Puttnam, do you still produce films?

No, I joined the House of Lords in 1997 and my last film came out in 1998.

Has cinema been the great passion in your life?

Yes. I was interested in connecting up my ideas with audiences. Most of the films I made originated from concepts that I started.

Were you surprised by the success of Chariots of Fire?

I was knocked sideways. My earlier film Midnight Express was extremely well received but did not reflect me or my values. Chariots of Fire on the other hand was almost an act of defiance, and a pivotal moment. No one was eager to make a film about 1924 Olympians running around in white shorts. It was not an obviously popular theme at the time.

Why did you make it?

To argue against the view that a decent person with a decent set of values was going to lose out in the great race of life. The protagonist Eric Liddell was a guy who did absolutely the right thing – and won. You don’t have to end up being a loser if you work through your conscience.

Did success allow you to do what you wanted?

Chariots allowed me to do a film about Northern Ireland called Cal, not a huge success but a good film. The Killing Fields was a big success for me. It won one of my two Donatellos. Then I made The Mission, which was also, I think, a fine film which won the other.

David Puttnam, why did you want to make a film of Inside the Third Reich, a book written by the Nazi architect Albert Speer?

Speer was a young, ambitious architect who made a political decision about his life very early on and joined the Nazi Party as a way of accelerating his career. It fascinated me, because if my country had been in the same catastrophic state that Germany was in the 1920’s and I was ambitious, I would quite possibly have been tempted to look around for where the opportunities lay. I felt empathy for the fact that he’d made a decision at that early point in his life that had catastrophic consequences. Sandy Lieberson and I met him several times, and he was good enough to decide that the film should be made by young people. I then hit all kinds of incredible roadblocks, and the film of Inside the Third Reich was never made, but we’d accumulated a vast amount of research over a period of two years, so we took all that research and financed two documentaries, The Double Headed Eagle and Swastika. In those films we tried to tell the story of how seductive the Nazi regime was at the time it emerged into power between 1929 and 1933, and what chaos Germany was itself in at that time.

Did the story of Albert Speer become a metaphor for you?

I’ve used it as a paradigm for years. Today we are similarly challenged. Unless we wake up and understand the fragility of democracy and that the ramifications of climate change are likely to ask huge questions of our democracies, then we are very likely to find ourselves travelling down the same road that Speer found himself on.

When you met him in Heidelberg was Speer repentant?

Yes, but more interesting was the point at which he felt he should have known better. He chose Kristallnacht in 1938 as the crucial moment for him. His architecture professor was a well-known Jewish architect, and Speer said, “I should have understood what was going on, but I was more worried about the destruction in the town and the glass in the streets and everything else – and I didn’t get it.” He should have understood much earlier, at the time of the burning of the Reichstag. For five years his moral compass had drifted, and because his moral compass didn’t correct itself he was a lost soul in 1938.

Was he flattered by the importance of being the architect of the Nazi regime and so close to Hitler?

Absolutely. A combination of flattery, hubris, all the things that many people – and I include myself – are vulnerable to. He fell for it, hook, line and sinker.

Why did you get involved with politics in the 1960s?

It was an era in which, if you were reasonably successful, you had to decide what side of the barricades you were going to stand on. I was of the President Kennedy generation, full of hope, full of optimism. Following his death, and the subsequent assassination of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy in 1968 it was hard not to become radicalized. In fact I rather despised people who weren’t prepared to set out a clear position for themselves.

Has Britain changed since the times of Chariots of Fire?

Britain is unrecognizable since the 2012 Olympic Games. It’s a country that has badly lost its confidence. This government is sleepwalking – or maybe worse than simply sleepwalking – into an era of authoritarianism which I find very uncomfortable, and which I feel the absolute necessity to call out.

David Puttnam, why did you title the report of a UK parliamentary Select Committee that you chaired Digital Democracy and the Resurrection of Trust?

I was originally going to call it The Restoration of Trust, but the evidence we took was so serious in terms of the breakdown of trust in public officials, almost in each other, that I felt it required a form of ‘resurrection’ to allow us to begin to re-emerge from the increasingly dark place in which the UK and many of the Western democracies find themselves. Although Italy is very lucky to have Mario Draghi. I’ve spent enough time with him to know he’s a fine and extremely principled man.

Will the UK find a way to refashion itself in its post-Brexit situation?

History will show Brexit to have been a catastrophe for the UK. I don’t think it’ll come out of this present situation well at all. The need at the moment is to attract people around the concept of trust. How do we rebuild trust? How do we recreate trust? If we could do that, then anything becomes possible. If we fail to re-create trust, it’s over.

Do you trust Keir Starmer, the leader of your own Labour Party?

Yes, I do. He has to resist the temptation to be pulled away from the center of his party but I think that’s his instinct and he is a decent, honest, truthful man. The Labour Party in effect took a poison pill when it elected Jeremy Corbyn and has still not recovered its confidence.

How well has the UK handled COVID-19?

It’s gone in waves. The initial handling was very bad, and eventually there will be a public enquiry which will establish that. The speed with which the jabs were created was impressive, but we’re in danger of falling back into complacency.

Is the strongest democracy in Europe still the British one?

My fear lies in the early consequences of climate change, and the refugee crisis that will accompany it. When the impacts of food and water scarcity really hit and migration to western Europe begins in a serious manner, that’s likely to prove – and this is very frightening – the perfect trigger for authoritarian politicians to argue, “We’ve got to stop this. We’ve got to stop these people.” I’ve no doubt that will happen; it’s how we as democracies deal with it that will determine our future as societies firmly based on social morality and the rule of law.

But British people will reject any system other than democracy?

I wish I could be sure of that. Under pressure, and frightened into the belief that the issue of climate migrants might become a determining factor in their lives, I don’t know what the British people would decide.

What are the issues in Britain today?

One, not sufficiently discussed, is the fragility of the Queen. The one element of cohesion in Britain at the moment is respect for the Queen. Her death would ask huge questions, particularly in Scotland, where she retains enormous affection. People don’t seem to fully realise how serious a crisis the death of the Queen could provoke.

David Puttnam, are you proud to have chaired the Committee that saw through the world’s first climate change bill in 2008?

Enormously proud. I’ve been involved in the environmental movement since the early 70s, so it’s a world I know well. I’m trying to get my colleagues to better understand the direct political correlation between the ramifications of climate change and the future stability of democracy.

Can we make the transition to Net Zero through technical and scientific progress?

Science can make some big wins for us, particularly in the area of energy, which is by far the greatest problem. But we also need to work on education, preparing young people to become more resilient and more understanding of what might be required of them. I’m also not aware of there being any contingency plans or funding in place to deal with what will be very real large scale emergencies. I once gave a speech comparing human beings to meerkats or gerbils; animals that are brilliant at alerting themselves to immediate danger but with little capacity to understand let alone act upon longer-term dangers. I’m afraid we as human beings are similar. We are pretty good at dealing with crises, but terrible at planning and anticipating them.

What discussions have you had about how best to handle the migration issues?

Not sufficient, because I’ve been very tied up in the environmental mitigation world. I would definitely like to do more work on these migration issues, initially through UNICEF, of which I was U.K. President for seven years from 2002 to 2009.

Why did you decide to live in Ireland?

I love the place, I love the people. It has spirit and ingenuity, and it has all the things that, growing up, I thought Britain had. I’ve been somewhat pessimistic about the UK for some while now. In 1988 when I came back from California I realised something had changed in me; that I was very much a European. I got closely involved with European cultural organizations. Twenty of us founded the European Film Academy and I became engaged in other cross-European media ventures; I felt very much ‘a European’ and still do. We originally purchased this house on the West Coast of Ireland as a summer home, but over the years we spent more and more time here, made more friends, and decided it was where we would live out our old age. Now we are now hopefully waiting for our Irish citizenship to come through.

You would rather be Irish than British?

I’d rather be European than British. As a kid I wanted to be an American, I will hopefully now die as a republican and a European!

Do the people of Northern Ireland feel British?

This is a moveable feast. If you allowed the Theresa May compromise to work its way through, and both sides of the border to operate harmoniously, I do believe it would lead to the evolution of a successful united Ireland, but it won’t happen in my lifetime.

Will Scotland and Wales also leave the union?

If I were a Scot, I would feel marginalized by England. There is no reason why Scotland shouldn’t be a perfectly viable economic entity, like Finland or Estonia. Scotland will ultimately leave the Union, but I can’t see how Wales can economically survive by itself. The possibility of Wales becoming a socially independent principality, whilst remaining within – I don’t know what they’ll call it – England/Wales, is more likely.

What is the reality of the ‘special relationship’ between the UK and the USA?

Since the beginning of the Obama presidency, it’s been growing much more distant. The British have to start getting rid of their illusions about that relationship. In parliament I tried to explain to the Brexiteers how the Senate and Congress worked, and that around 11 members of the Senate and 31 members of Congress self-identify as Irish-American. Those people will not go before their electorates and support a situation in which the Good Friday Agreement is under threat. Pushing through a trade deal against a strong Irish-American congressional block was always a total fantasy.

What about the UK’s relationship with China?

The U.K.’s relationship with China is chaotic. China is a country that’s historically reluctant to break treaties. The UK and Boris Johnson’s apparent indifference to the sanctity of international treaties is quite different from their culture, which must really puzzle and ultimately disturb the Chinese.

It seems the Chinese are generally disappointed by Europeans, while America is at least a clear competitor?

China stole all of our capitalist clothes but didn’t bother to embrace our version of democracy. Historically China has always imploded from within, so their principal concern is internal stability. The leadership fully understand the consequences of an internal societal implosion. They should be focusing on trying to close the gap between the relatively wealthy southeast of the country and the relatively poor northwest. The danger is that in order to create greater cohesion they may seek to inflame external tensions.

Could China become a threat to world peace?

At some point beyond my life span the score between China and Japan will likely be settled. The relationship with Korea has also never been fully reconciled. What surprises me is that China hasn’t been more patient. I would have expected the sort of belligerence that we’re seeing from China to have waited for at least another decade. Unless their internal situation is more fragile than I’ve been led to believe, then I don’t see what their rush is.

Do you have another film project that you would like to achieve?

How wonderful it would be to become the world’s oldest film producer! I’d like to have made a big musical, and I always wanted to make a film about the First World War, trying to show how that ghastly conflict had its roots in the mistakes and misadventures of international diplomacy. The truth is that well-intentioned people, sitting down and understanding the fears and expectations in each other’s hearts, can achieve more than we realise.